RuPaul's Drag Race All Stars Episode 3 Recap with Nathan Jurgenson

A look at "Drag Race" with an academic.

Here are Nathan Jurgenson's notes...

Okay, I’m watching "RuPaul’s Drag Race" for the first time for Brandon Wetherbee’s podcast, and am typing up notes as I go [I’ve edited them for use on this blog]. I’m drinking a Manhattan and eating chocolate ice cream. I knew a little of the show before seeing this first episode; well, it’s my first, though the show has been on for years and this is Season One Episode Three of the “All Stars” spin-off. Here goes.

My first reaction is that the show looks/feels/sounds/behaves a lot like other reality shows I’ve seen. Somehow I was expecting something a little less formulaic. I can’t tell yet if this is a satirical spoof on the genre or uncreative adherence (the same debate some have over, say, Lady Gaga’s image). I laughed out loud at the “Tran Drescher” joke.

The show has four segments: a first challenge, a second challenge, and a backstage moment getting ready for the fourth part, a fashion showdown, lip-sync competition and final elimination. The first challenge was fascinating at the level of gender and sexuality norms and performance and, to get real nerdy, a sort of meta commentary of the reality television genre itself. Stay with me. The contestants are given a camera and asked to take a “selfie” of themselves looking as butch as possible. The result is a sort-of meta photographic identity performance.

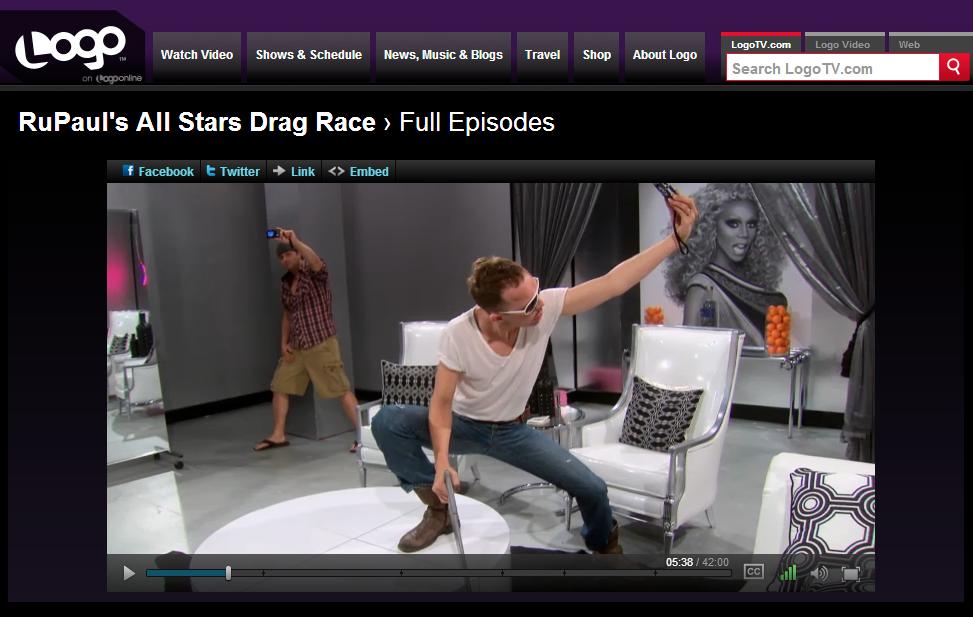

By this I mean the viewer is watching via a camera a contestant who himself is holding and posing for another camera. The scene makes obvious the performance for the camera inherent in all so-called “reality” television. No one is naive enough to believe that the camera doesn’t change how people behave. That the “reality” in Reality TV is false is a truism. The show plays with this fact, providing symbolic irony of people with cameras pointed at them given a camera to hold and point back at themselves. Actually, the show takes this one step further, see the screenshot I took below:

Consider the camera-mediated sightlines at play here: the viewer at home is watching through one camera; we see an individual posing for a second camera; and the fourth wall is broken when another individual in the background snaps a photo of the original camera, completing a circle of photographic vision. The photo snapped in the background here is a photo of a photo of a photo; the photographic gaze emanates from the home viewer onto an individual, back into his camera, back to him, and ultimately back at us.

Or maybe this is reality? Maybe posting on Facebook is a lot like posing for the Reality Television cameras? Maybe all of our lives, on and offline, camera present or not, take on this form; maybe we are increasingly living as if we are part of a reality television cast, understanding our present as something worthy of broadcast, or at least a status update? Perhaps it is Reality TV that is then most real in its garish embrace of simulated unreality? If any of this is true, "Ru Paul’s Drag Race" is about the realist thing we’ve got.

Manhattan number two and the show moves onto its second segment which involves doing craayzee behavior on the streets for what we are told (but don’t for a second believe) is a “hidden” camera. This segment feels uncomfortable because the contestants often feel uncomfortable. The creative and empowering and non-normative and entertaining and gorgeous identity fashioning thrives in safe spaces, but starts to wear at the edges when the contestants are put on a public street under harsh daylight to make a fool of themselves for those passing by. This, of course, isn’t to say that gender-play doesn’t belong in the streets, but that when contestants are uncomfortable pushing the limits of safety for the amassing of “points” and the entertainment of the viewer, it feels a little off.

The most uncomfortable moment of this segment is when a contest is supposed to ask a passerby for $5 and they all have a big laugh at not asking a person who looks like they do not have much money. The show is above this, and it’s above this type of public humiliation.

But then the show moves onto my favorite moment. In fact, if the whole show was this third segment, I’d watch every week. The segment takes place “backstage” in a dressing room where the contestants create outfits and do makeup. I was disappointed that the show skipped showing the creative process behind the extraordinary outfits. But what is seen is a downright touching discussion between the contestants talking about their insecurities, society’s expectations, and much else. They comfort each other and celebrate a positive self-image. This backstage area (as well as the costumes being created and the performances about to happen) serve as a positive and supportive space. I mean, I don’t know the last time I saw a group of men talking about their insecurities and supporting each other. This was "Drag Race" at its most charming.

The show is almost over, and prizes have been given away. Underwear of the month, shoes, the show is highly commercial, highly consumerist. Perhaps that is not surprising given the focus on fashion, but there is some irony that the fashion industry is often (but not always) a primary source of normative images around gender and sexuality.

The show is over, making one last Manhattan, and trying to collect some concluding thoughts…

"Drag Race" strikes me as the opposite of many reality shows in one respect: if most reality shows are about what you can do if you go out into and changing the world (think: "The Apprentice"), "Drag Race" is about changing oneself. Not as outside-looking but instead inward: the goal is to construct and maintain the self, keep it happy and in good working order, to come to know and appreciate yourself.

As much as I like this, I walk away with a bit of an unsettled feeling, even though "Drag Race" seems to be all about “FUN!”

"Drag Race" is the kind of fun where everyone at the end is crying.

The show, centrally, is a competition. It is equal parts support and judgment. Behind the underlying message to “love yourself” is a constant stream of judgment and critique. The winners are those who are the most “well behaved”, those who conform to the rules more than their competition. The losers are those who cannot live up to the standards of the judges (not metaphorical judges, but literal judges gazing always on the contestants, ready to provide constant critique of the minutia of every behavior, ready to dole out punishment at will).

Individuality is celebrated, in theory, but in practice what is rewarded is being individually the most conformist to the prescribed set of rules that anthropomorphize into the almost frighteningly judgmental Ru Paul character. I felt some fear that what I was watching was play made work, difference made sameness, fierceness made docility, creativity made ordinary.

But isn’t that how it always works? Creativity, self-expression, play almost never can be achieved on their own terms. Indeed, it is only from a position of privilege that one can even hold that as a possibility. Hopefully these contestants can learn to play this game, and all the conformity that comes with it, and come away in a better position to never have to do that again. That’s reality, for everyone, to have to learn to behave so, just maybe, we’ll never have to behave again.